KENDRA BULGRIN

May 25 – July 31, 2020

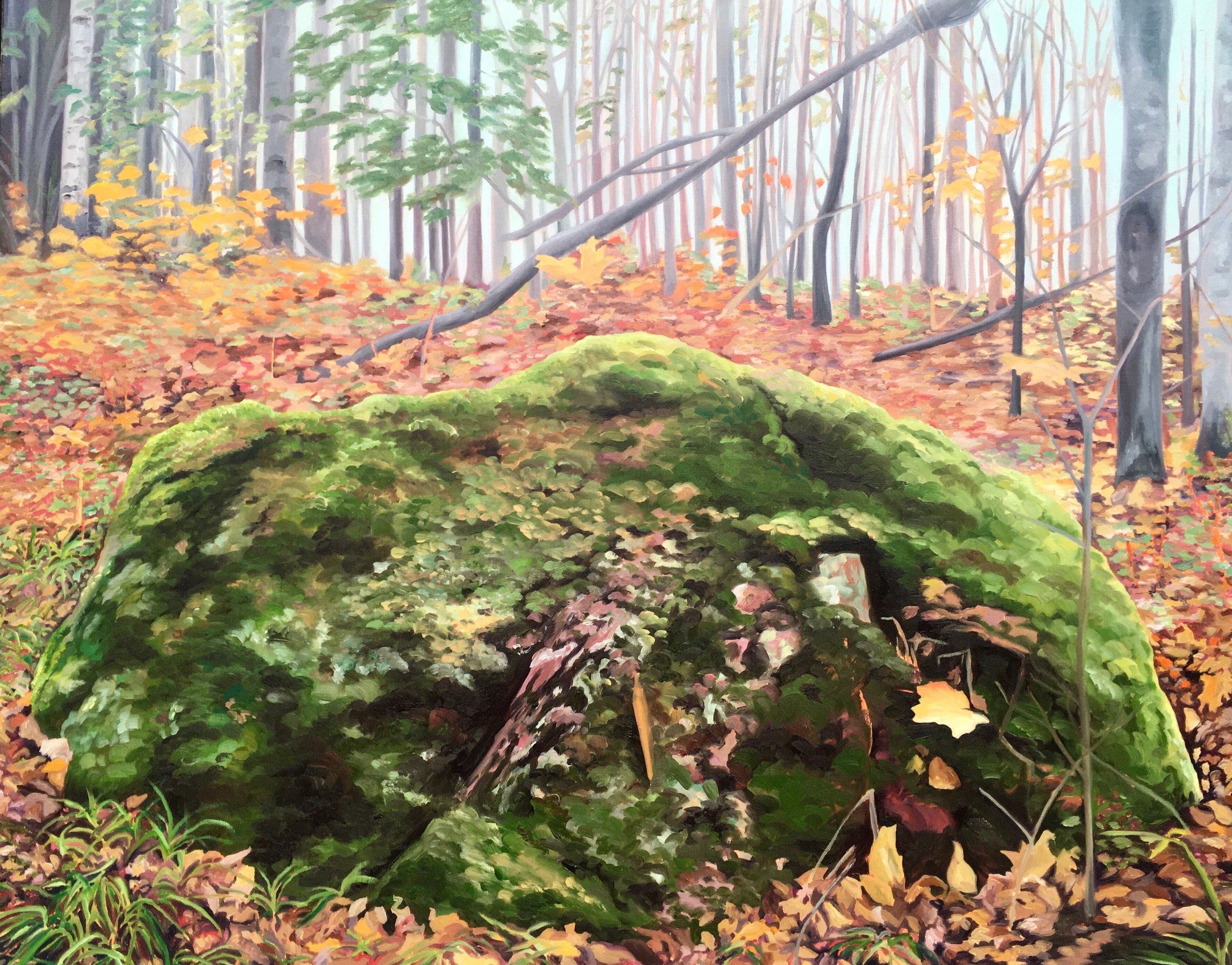

Kendra Bulgrin’s oil paintings examine the longing for identity and the subsequent expectations associated with identity and memory, questioning how identity is constructed through images, place, memory, decoy, and the miniature.

ARTIST STATEMENT

My oil paintings examine the longing for identity and the subsequent expectations associated with identity and memory. I question how identity is constructed through images, place, memory, decoy, and the miniature.

In recent work I have been using decoys and taxidermy as stand-ins for the “real” as I once used miniatures. They are another way to think about the “real and ideal” and the relationship between human and animal. I am also interested in human expectations concerning our relationships with animals and nature. Our imagining of animals stems partly from our cultural environment and can be linked to our imagining of self and family. There is a longing to know our selves through animals. Animals make us more human.

I have also always been interested in the metaphorical implications of simulation and mimesis. The decoys are life-sized, meant to mimic nature and often used in hunting to lure in or get closer to wild animals. I have been thinking a lot about how humans long to be closer to nature and continually return to it as a place of rejuvenation as we become increasingly detached from the natural world. Yet actual closeness with wild animals is difficult or nearly impossible to achieve except in captivity. I use the decoys as metaphors for my own feelings of detachment from family, nature, memory, and my own natural roots, and my desire to feel connected.

The landscapes are inspired by remote locations throughout Wisconsin that I have felt a strong connection with. I find myself attracted to the repetition of certain icons in the forest and on the water that I tend to photograph a lot and then bring back into my studio to create paintings from. They are also inspired by Tom Uttech’s work and the recent exhibition at the Wisconsin Museum of Art in West Bend. The figure tends to re-appear and disappear throughout the landscapes creating a dialogue between the absence and presence of WOMAN in nature. There is a deep mystery in nature that I long to connect with and I hope my paintings give glimpses of that.

This new work is inspired by Susan Stewart’s Poem, “Four Questions Regarding the Dreams of Animals”. One of my favorite poems right now.

1. Is it true that they dream?

It is true, for the spaces of night surround them with shape and purpose, like a warm hollow below the shoulders, or between the curve of thigh and belly.

The land itself can lie like this. Hence our understanding of giants.

The wind and the grass cry out to the arms of their sleep as the shore cries out, and buries its face in the bruised sea.

We all have heard barns and fences splintering against the dark with a weight that is more than wood.

The stars, too, bear witness. We can read their tails and claws as we would read the signs of our own dreams; a knot of sheets, scratches defining the edges of the body, the position of the legs upon waking.

The cage and the forest are as helpless in the night as a pair of open hands holding rain.

2. Do they dream of the past or of the future?

Think of the way a woman who wanders the roads could step into an empty farmhouse one afternoon and find a basket of eggs, some unopened letters, the pillowcases embroidered with initials that once were hers.

Think of her happiness as she sleeps in the daylilies; the air is always heaviest at the start of dusk.

Cows, for example, find each part of themselves traveling at a different rate of speed. Their bells call back to their burdened hearts the way a sparrow taunts an old hawk.

As far as the badger and the owl are concerned, the past is a silver trout circling in the ice. Each night he swims through their waking and makes his way back to the moon.

Clouds file through the dark like prisoners through an endless yard. Deer are made visible by their hunger.

I could also mention the hopes of common spiders: green thread sailing from an infinite spool, a web, a thin nest, a child dragging a white rope slowly through the sand.

3. Do they dream of this world or of another?

The prairie lies open like a vacant eye, blind to everything but the wind. From the tall grass the sky is an industrious map that bursts with rivers and cities. A black hawk waltzes against his clumsy wings, the buzzards grow bored with the dead.

A screendoor flapping idly on an August afternoon or a woman fanning herself in church; this is how the tails of snakes and cats keep time even in sleep.

There are sudden flashes of light to account for. Alligators, tormented by knots and vines, take these as a sign of grace. Eagles find solace in the far glow of towns, in the small yellow bulb a child keeps by his bed. The lightning that scars the horizon of the meadow is carried in the desperate gaze of foxes.

Have other skies fallen into this sky? All the evidence seems to say so.

Conspiracy of air, conspiracy of ice, the silver trout is thirsty for morning, the prairie dog shivers with sweat. Skeletons of gulls lie scattered on the dunes, their beaks still parted by whispering. These are the languages that fall beyond our hearing.

Imagine the way rain falls around a house at night, invisible to its sleepers. They do not dream of us.

4. How can we learn more?

This is all we will ever know.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Born in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, KENDRA LYNN BULGRIN attended the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater where she received a BFA with an emphasis in painting and a minor in Japanese Cultural Studies in 2005. She completed her MFA in interdisciplinary arts at Memphis College of Art in 2007. Bulgrin draws from a unique vantage point as an adopted child and continues to explore the complex issues surrounding her identity, memory, and past. Recently, she has been exploring motherhood and coming to terms with the birth and the ongoing care of her two sons, both with special needs. Bulgrin has shown nationally and internationally, with shows at the Brooks Museum of Art (Memphis, Tennessee), Hardy Gallery (Ephraim, Wisconsin), and at Beijing Normal University (China). Bulgrin has taught everything from Painting to Design at Memphis College of Art, Washburn University, Emporia State University, University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, and St. Norbert’s College. Currently, she is the director and owner of James May Gallery. www.kendrabulgrin.com